Keep the Home Fires Burning

The association of music with conflict is legendary, and the First World War is no exception. Never Such Innocence on 3 November looks back at some of the extraordinary writings and music that emerged from this period….

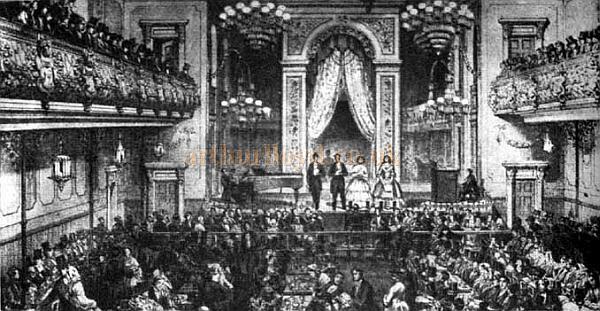

Prior to 1914 the Music Hall was the centre of popular cultural life with ever larger theatres of up to 2000 seats staging live musical acts alongside animal imitators, acrobats, human freaks and conjurors. This was before the days of the affordable gramophone and so cheap seats at a show provided access to a new repertoire of populist songs.

The stars of the day ranged from the jauntily comic to the bawdy performer such as the likes of George Formby (pictured) and Harry Lauder.

During the war years alone the Music Hall was the perfect platform for several thousand new music hall songs. A real hit could sell over a million copies.

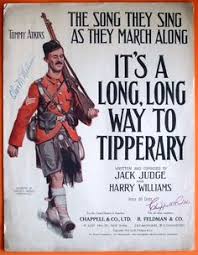

At the outbreak of war, many songs encouraged young men to join up with tiles such as We Don’t Want to Lose You, but We Think You Ought to Go and It’s A Long, Long Way to Tipperary.

But after a few months of war with rising numbers of casualties these recruitment songs all but disappeared.

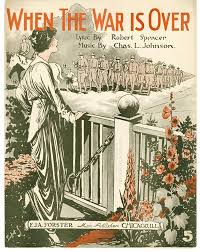

Increasingly these music hall songs focused on dreams about the end of the war such as Ivor Novello’s When the Boys Come Home and Keep the Home Fires Burning.

Songs often portrayed soldiers as brave and noble, while the fragile and loyal women waited patiently at home for their loved ones.

In the world of British classical music the war coincided with a time of transition. The older generation of composers such as Parry, Stanford and Elgar would normally have been overshadowed by a younger generation of composers. Ivor Gurney, Arthur Bliss and Herbert Howells were all students in 1914, but as many of these were of enlistment age they were sent to the front and of course many of them never returned. Of those composers who went to fight, George Butterworth, F S Kelly, William Denis Browne, Ernest Farrar, Willie Manson and Cecil Coles tragically did not survive.

‘A very special, moving and immensely absorbing production’

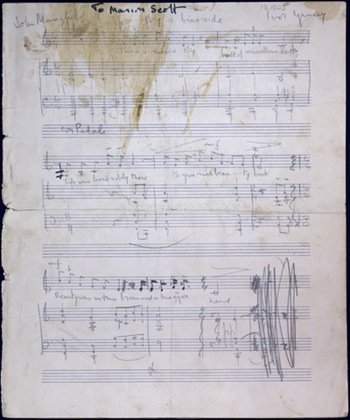

Although difficult for composers to write whilst on active service, the pieces they did write are a barometer for the times. Ivor Gurney, returning after 15 months at the front, having been shot and gassed, brought with him five of his most enduring songs. One mud-spattered manuscript, a setting of By a Bierside, was written by the light of a stump of candle in a trench mortar emplacement.

There were demands such as in The Musical Times for the composers of the day to write music which commemorated, celebrated and raised the spirits of the Nation. Elgar’s The Spirit of England, for example,was initially popular but but as the mood of the nation turned peoples’ emotional needs changed to a desire for music which expressed people’s grief, and served as a memorial to those who had been lost.

After the noise of war fell silent at 11am on 11 November 1918 it was left to the older generation to reflect on the conflict and to pay homage to its memory. For example, Vaughan Williams after serving with the Medical Corps in France, wrote his achingly beautiful Pastoral Symphony in 1922 as a monument to loss, with bugle calls echoing across the French landscape.

Never Such Innocence captures the spirit of the age in a moving narrative recital of words and music from the First World War delivered by professional actor Christopher Kent and pianist Gamal Khamis.

THE RECITAL SERIES

Never Such Innocence

Saturday 3 November 7.30pm

St Michael’s Church, Broad Street, Bath BA1

Tickets are just £16 (or £15 in advance with a discovery card)

‘Beautifully nuanced show – tender, moving, angry”

With generous support from